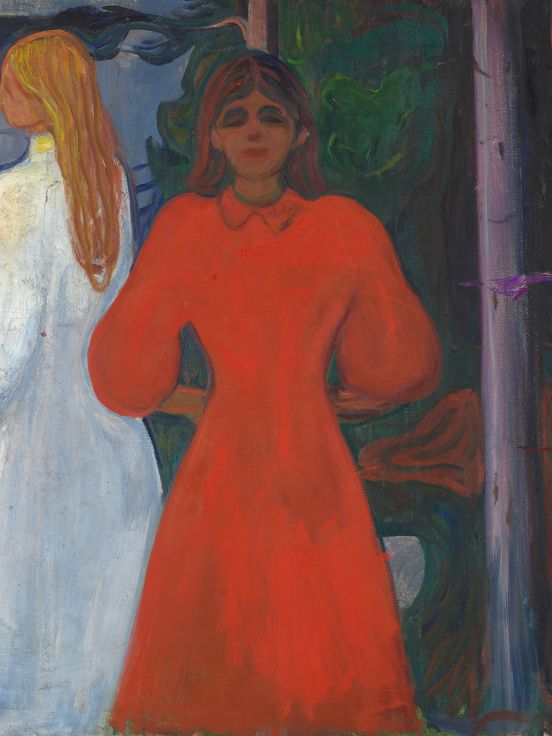

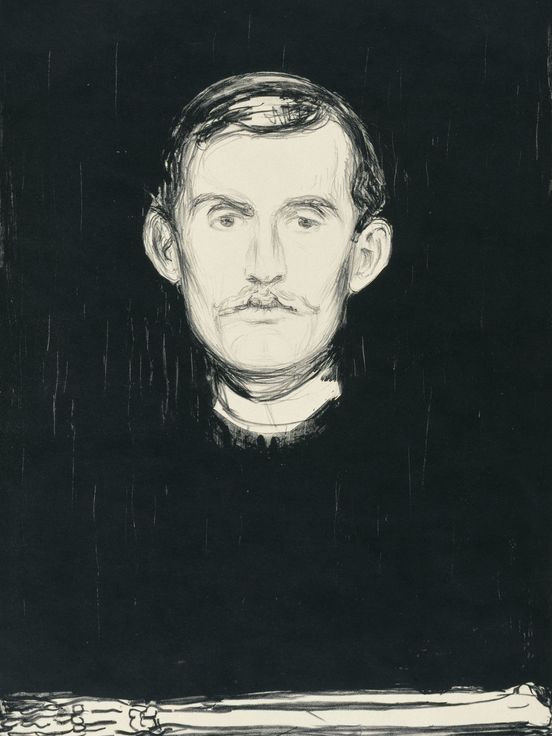

The “Munch Affair“

In the late 19th century, Berlin was gripped by a fervour for everything Nordic. “Germany’s best, all the creative literature around the turn of the century, succumbed to the magical enchantment of the North,” recalled writer Stefan Zweig in 1925. The fascination spread to the fine arts, prompting the Association of Berlin Artists to invite Munch, still largely unknown, to stage a solo exhibition in November 1892. The suggestion had come from another Norwegian artist, Adelsteen Normann, a resident of both Berlin and Norway. Normann specialised in popular fjord landscapes that sold extremely well. Indeed, the German Kaiser – Wilhelm II – was among his customers.

Berlin’s art community was not very progressive back in the early 1890s. Mainstream taste was governed by prestige and tradition, an attitude that was championed by Wilhelm II and the influential painter Anton von Werner, who presided over the above-mentioned Verein Berliner Künstler. The 55 works by Munch that went on display at the House of Architects on Wilhelmstrasse were so avant-garde and alien that they hit the art community like a meteorite and tore it in two. Established members of the association were outraged and applied to have the exhibition closed down at once. And so, only a few days after the opening, the show was dismantled again. The “Munch Affair”, as it was ironically tagged by the press, marked the advent of modern art in the city. Munch, not yet thirty, revelled in the unexpected publicity. He wrote home: “It is, by the way, the best thing that could happen, I can have no better advertisement.” He moved at once to the banks of the Spree, where he spent several long periods living and working between 1892 and 1908 before settling in Norway from 1909.