Abstract painting with no reference but itself – for a long time after the Second World War this remained the creed in the Federal Republic of Germany and West Berlin. In the 1960s this creed was radically challenged by young artists.

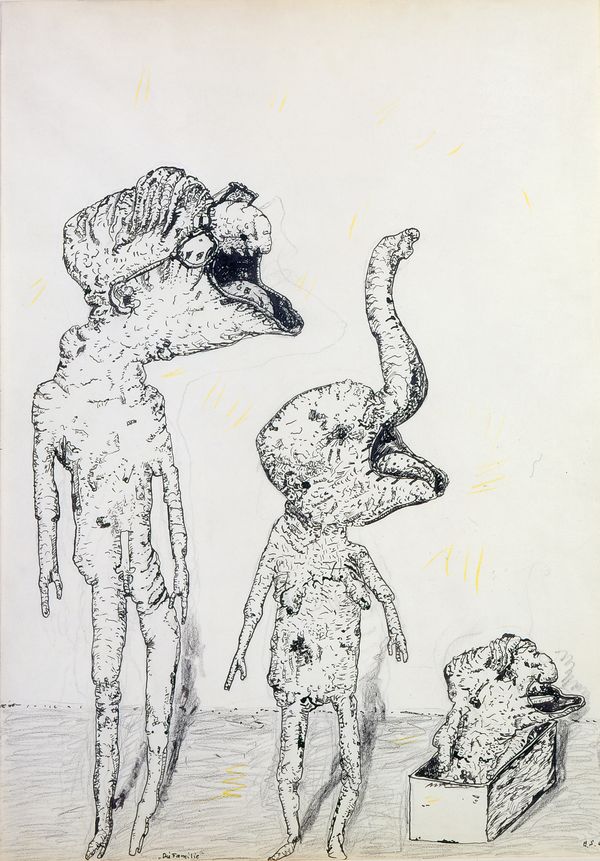

Eugen Schönebeck, The Family, 1963

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2019They wanted to restore objects and figures to art – but without lapsing into a style that would evoke the disastrous Nazi past or the Socialist Realism cultivated in the German Democratic Republic. They developed a new, critical form of figurative painting known as New Figuration or Critical Realism. Its exponents were highly critical of post-war society with its denial of historical trauma, its social conformity and its unspoken anxieties. And so Eugen Schönebeck and Georg Baselitz published their “Pandemonic Manifesto”, embracing the ugly, the obscene and the blasphemous as key themes in their painting. New exhibition formats were likewise tested. In the mid-1960s, for example, a group of artists founded the first self-help gallery, Großgörschen 35. It proved to be a model for many artists seeking to market their own art.

Artists fascinated by the Dada heritage were motivated by a similar desire to forge closer links between art and life. Back in the 1920s Dada had incorporated everyday objects and newspaper cuttings. Another source of inspiration now was Pop Art in the United States and Britain, which adopted elements of popular culture and visual strategies used in comics and advertising. Some artists attacked attitudes to the Nazi past or an art world driven by profit. Wolf Vostell and the American couple Edward and Nancy Kienholz, who began to spend a part of each year in Berlin from 1973, devoted significant installations and environments to these issues.

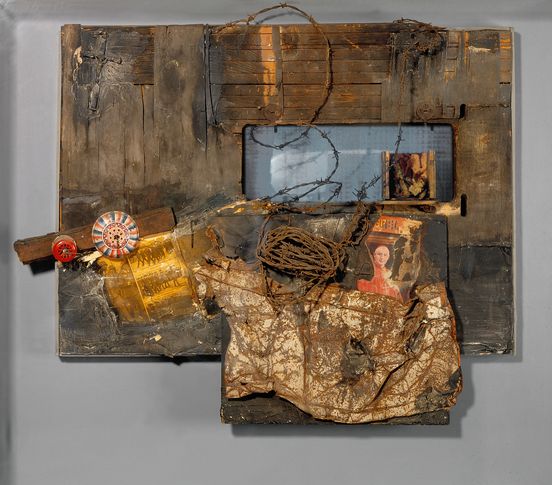

Edward Kienholz and Nancy Reddin Kienholz, The Art Show, 1963–77

© Nancy Reddin Kienholz