When the National Socialists assumed power in early 1933, the lively, diverse avant-garde scene came to an end, even in Berlin. Joseph Goebbels, the Minister of Public Education and Propaganda and simultaneously President of a newly created Chamber of Reich Culture, was now in complete control of cultural affairs.

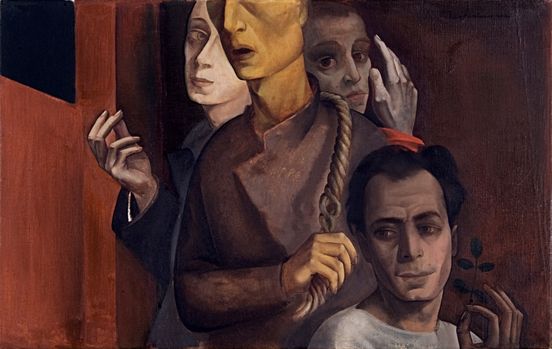

Rudolf Schlichter, Blind Power, 1932/37

© Viola Roehr-von Alvensleben, MünchenHe wanted “German” art made by people of “Aryan” descent. Works by Modernist, Jewish or dissident artists were discredited as “degenerate” and their creators were stigmatised as “cultural Bolsheviks”. Many of these artists were banned from teaching, exhibiting and painting by the Nazi regime. Their works were removed from public collections and sometimes sold abroad. Many artists were persecuted, arrested and killed. Some managed to escape to other countries. Many who remained in Germany bearing the shameful “degenerate” tag lived in isolation and continued their work in secret.

Others in turn adapted to their new masters and placed their art in the service of the Nazi dictatorship. Buildings like the New Reich Chancellery designed by Albert Speer exposed the megalomania of the self-declared “Thousand-Year Reich”. Berlin was to be developed as “the world capital Germania”. Sculptor Arno Breker supplied fittingly colossal and heroic figures. More than any other artist he embodied a form of art that was regarded as ethnically authentic and known as “völkisch”. Photographers such as Erna Lendvai-Dircksen also adopted this racist ideology of ethnic supremacy, translating it into an aesthetic of heightened pathos. Some of their stylistic devices were drawn from New Vision photography. There was huge demand for such images. With the aid of technically sophisticated, skilfully choreographed pictures, the illustrated press, exemplified by the popular magazine “Volk und Welt”, sought to present the Nazi state as progressive and modern.