Living material

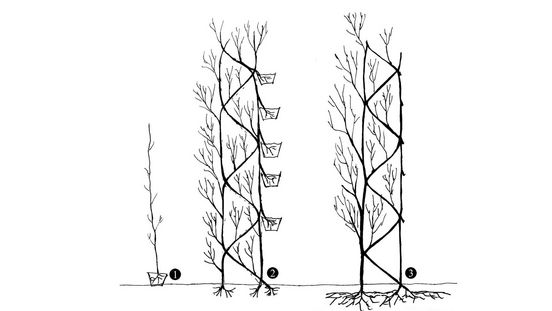

For over 1,000 years, the Khasi, an indigenous people who live in north-eastern India, have been building bridges from the aerial roots of rubber trees. These are used to cross rivers and valleys, and they can also withstand earthquakes. The bridges are maintained and improved for generations.

In Europe, lime trees often served as public venues. Dances and festivals were held in their crowns. The “dance lime” or “tilleul à danser” was at the heart of many a village and its folklore. In 2017 a “Tanzlinde” was planted on the disused Tempelhof airfield in Berlin.

Arthur Wiechula, a landscape engineer in Berlin, argued in the 1920s that any kind of building could be constructed out of trees. He claimed that by pruning he could train them to merge and create closed spaces. None of Wiechula’s adventurous arbotectures were ever built.

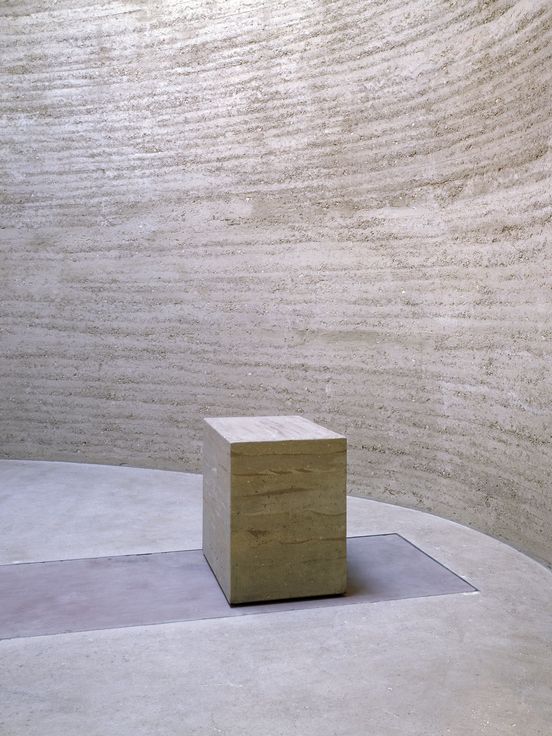

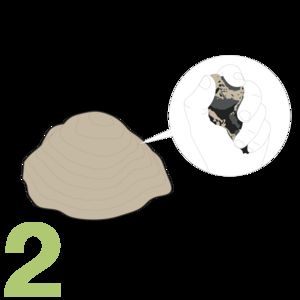

For a long time, building close to nature was seen from a Eurocentrist, evolutionist perspective as sentimental hankering for the remote past. Theoreticians of architecture, especially in the 18th century, regarded the “Primitive Hut” – built entirely of natural materials using the simplest methods – as the first sign of a cultural technique aimed at creating habitable space. It was an ambivalent ideal, illustrated here by a “Primitive Hut” in a stand of natural trees.